African American Cultural Trail of Greenville-Pitt County

The African American Cultural Trail of Greenville-Pitt County was created to celebrate the rich history and recognize the many contributions that African Americans made to the growth and development of our city and county. The trail allows you to experience the lives, stories, and history of our area’s early black educators, medical professionals, cultural leaders, and residents.

Take the journey and learn about the vibrant Downtown neighborhood before urban renewal, see the site where the first colored hospital stood, walk in the steps of the those who enjoyed the entertainment and social center of the African American community called “The Block” and enjoy the beauty of the Sycamore Hill Gateway Plaza where a group of 22 faithful individuals established Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church in 1865 after holding meetings in Sister Ruth Armond’s home on North Greene Street since 1860.

Explore the African American Cultural Trail of Greenville-Pitt County on a self-guided walking tour!

Download the African American Cultural Trail of Greenville-Pitt County Brochure

Download the Visit Greenville, NC App on the Apple App Store or Google Play to follow along the African American Cultural Trail for more information and audio interviews.

Images courtesy of Special Collections, East Carolina University, digital.lib.ecu.edu

Stop 1: Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church

Location: Sycamore Hill Gateway Memorial - 100 East First Street, Greenville

The Sycamore Hill Gateway Plaza is built on the corner of First and Greene Streets where the prominent Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church once stood. The Plaza commemorates the history of the African American community located Downtown in the area between the Tar River and 4th Street to the south including the Town Common and from Greene Street to Reade Street east.

Founded in the winter of 1860, the initial congregation of 22 members met at the home of Sister Ruth Armond on North Greene Street. In 1865, after the Civil War and 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, the founding members emerged and publicly established a physical home for the church, which was known as the “African Baptist Church" until the 1880's. Because of the presence of sycamore trees on the property, Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church was then chosen as its name.

Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church was the most significant institution in the community. The church was the center of religious, social, political, and economic activity for more than 100 years on this site.

The congregation relocated twice, and the current church is located at 1001 Hooker Road in Greenville.

Listen to Interview with: Ann Floyd Huggins - ECU Digital Collections

Listen to Interview with: Darlyn Crandell, Linda Coleman, and Geraldine Dudley - ECU Digital Collections

Listen to Interview with: Evelyn Lopez, Christopher Randolph, Sr., and Alexander Randolph - ECU Digital Collections

Stop 2: Town Common & Urban Renewal

Location: Sycamore Hill Gateway Memorial - 100 East First Street, Greenville

The Downtown neighborhood was a close-knit African American community that included homes, businesses, and the Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church. Descendants describe the area as thriving and vibrant with a high quality of life.

The Housing Act as amended in 1949 created new national goals for decent living environments, funded "slum clearance," and urban renewal projects, and national public housing programs. This led to the creation of the Redevelopment Commission of the City of Greenville (December 1958) by the City Council. The commission's first task was the Shore Drive Redevelopment Project N. C. R-15 (February 1960). The Shore Drive Redevelopment Project was to revitalize Greenville's downtown area.

Listen to Interview with: Charles Gatlin - ECU Digital Collections

Listen to Interview with: Lucille W. Gorham and Lucille Gorham Sayles - ECU Digital Collections

Listen to Interview with: Alton Harris - ECU Digital Collections

Stop 3: Early Black Health Professionals

Location: 110 Evans St, Greenville

(on the corner of Evans & Second Streets)

On October of 1923, Miss Frances Hopkins, a well-known black nurse in Greenville opened her home at 114 N. Washington Street as a unit of Pitt General Hospital for colored patients. She began with two patients in a room in her house.

In early 1924, the Greenville Kiwanis Club began to work to open a black hospital in Greenville. They rented the Old Bernard House near the corner of First and Evans Streets and hired Miss Hopkins, a graduate nurse and Greenville native to manage it. The Kiwanis Club approached both white and black churches for donations and the Pitt General Hospital agreed to share their sterilizing plant, operating rooms, X-ray and pathological laboratories. Thus, the St. Frances Hospital for Colored People opened on September 1, 1924 with 15 beds and a staff of 2 graduate nurses and a few nurses in training.

Listen to: Oral History Interview with Dr. Andrew Best February 17, 1999 - ECU Digital Collections

Listen to: Oral History Interview with Dr. Andrew Best March 3, 1999 - ECU Digital Collections

Stop 4: Arts & Culture

Location: 404 South Evans Street, Greenville

(in front of Emerge Gallery & Art Center)

Johnny Wooten impacted tens of thousands of students and community members during his thirty-year career as a music educator and performer. Wooten also played a pioneering role in desegregation of East Carolina College through the musical performances he participated in during the late 1950’s following the ECC Board of Trustees’ decision to allow African American entertainers on campus.

The latter decision was prompted by the unexpected appearance of an African American musician as part of a Dave Brubeck concert in early 1958. While the line had been crossed, the Brubeck concert presented desegregation in unexpected and unofficial ways: one of the band members had fallen sick, resulting in a substitute musician who happened to be African American. Student response to the surprise development on stage was overwhelmingly supportive, encouraging the Board of Trustees to approve, officially and publicly, of African American performers on campus.

Stop 5: The Block

Location: 629 Albemarle Avenue, Greenville

(across from the Roxy Theatre)

This section of Albemarle Avenue was called “The Block.” It comprised approximately a city block and a half in length and housed many black businesses. There were a few freestanding buildings in the area that were associated with “The Block.”

“The Block was one of the main attractions in the city. We got out, we’d be going to The Block. That place was lit up. That’s what you did. They had the theatre, the restaurants, and barber shops.” - E.H. Eaton

“It was famous all over the world from all the soldiers in Europe. They’d hear you were from Greenville and want to know about The Block.” - Millard Bell

Listen to Interview with: Michael Garrett - ECU Digital Collections

Stop 6: Early Black Educators

Location: 400 Nash Street, Greenville

(in front of the old C.M. Eppes High School)

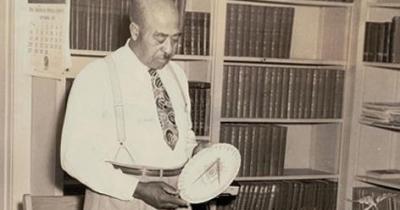

One of Eastern North Carolina’s most extraordinary friends in the cause of education in the first half of the 20th century was Charles Montgomery Eppes (1858 - 1942), supervising principal of Greenville’s African American schools from 1903 - 1942. A follower of Booker T. Washington’s (1856 - 1915) accommodationist approach to pedagogy and race relations, Eppes advocated hard work, racial self help, and public harmony with the white leaders of the day in the process. Eppes helped coordinate major improvements in African American education in Greenville and much of the state.

By the time of his passing in 1942, Eppes had outlived and out-served, as a teacher-administrator, all his peers, black and white, establishing a state record, unbroken still, of 65 years of active service as a public school educator.

Listen to: Mary Virginia Jones oral history interview, November 11, 1997 - ECU Digital Collections